Hemostasis models play a vital role in medical education and first aid training, providing a safe, controlled environment for medical personnel to practice and improve hemostasis skills. However, the question of whether these models are sufficiently focused on patient experience needs to be explored in depth from multiple dimensions.

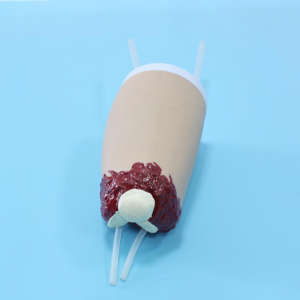

First of all, from the original intention of the model design, its main purpose is to simulate the real trauma situation, so that medical personnel can practice repeatedly in the simulated environment, so as to improve their ability to respond to the actual emergency situation. In this process, the designers of the model usually strive to reproduce the real wound morphology, bleeding conditions, and the surrounding tissue response to ensure the fidelity and effectiveness of the training. However, such designs tend to focus more on the technical level of simulation, and to some extent ignore the non-physical aspects of the patient experience.

Secondly, from the perspective of patient experience, the real trauma of a severed limb is often accompanied by severe pain, fear and anxiety and other negative emotions. These emotional reactions will not only affect the physiological condition of patients, but also may interfere with the treatment work of medical staff. However, in simulation training, because the model itself does not have vital characteristics, it cannot truly simulate these emotional responses of patients. As a result, medical staff may not be able to fully experience the pain and discomfort experienced by patients in simulation training, so that it is difficult to give patients sufficient psychological support and comfort in actual treatment.

However, this does not mean that the design and use of traumatic limb hemostasis models completely ignore the patient experience. In fact, with the continuous development of the concept of medical education, more and more educators begin to realize the importance of integrating humanistic care into simulation training. They began to try to incorporate elements into the design of the model that could guide the health care staff to pay attention to the patient's feelings, such as simulating the patient's voice, facial expression or physical response to remind the health care staff to maintain empathy and patience during treatment.

To sum up, although there may be certain limitations in the design and use of traumatic limb hemostasis models, which cannot completely simulate the real experience of patients, with the progress of medical education concepts and the continuous development of technology, we have reason to believe that these models will pay more and more attention to patient experience and provide a more comprehensive and real training environment for medical personnel.